Introduction to the dictionary

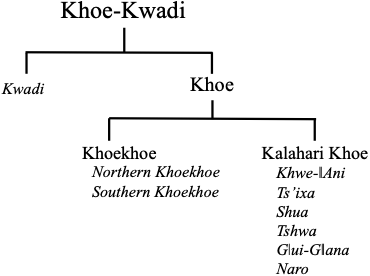

Khoe-Kwadi is one of the three southern African language families with inherited click consonants that were included in Greenberg’s (1963) macro-phylum “Khoisan”.

At present, Khoe-Kwadi languages are primarily spoken in Botswana and Namibia, but remnant speech communities also exist in Angola, Zimbabwe and South Africa (Figure 1).

Along with languages of the Kx’a and Tuu families, Khoe-Kwadi constitutes the Kalahari Basin typological area which is characterised by shared phonological, morphosyntactic and semantic features (Güldemann 1998; Güldemann & Fehn 2017; Nakagawa et al. 2023a). While the click languages of southern Africa are frequently associated with “San” hunter-gatherers or “Bushmen”, Khoe-Kwadi is not exclusively spoken by foragers but also by groups of cattle herders who once occupied the western half of southern Africa and were referred to as “Khoi” or “Hottentots” by early European travellers. In this context, it has been suggested that Khoe-Kwadi was introduced from outside the area by Late Stone Age pastoralists originating in eastern Africa (Güldemann 2008; Fehn et al. 2022).

At present, most Khoe-Kwadi languages of which we have knowledge are either severely endangered or extinct (Brenzinger 2013). Only Khoekhoegowab primarily spoken in Namibia still counts more than 150,000 speakers and is featured on national media, as well as in a restricted set of educational contexts.

Research history

The first descriptions of Khoe-Kwadi languages date back to the 17th century and relate to now-extinct varieties spoken by herders in the Cape region of South Africa (den Besten 2010). However, it was not until the early 20th century that the close relationship between the languages of the herders and a subset of forager languages spoken across Botswana and Namibia was recognized, leading to the establishment of the “Khoe” or “Central Khoisan” family (Dornan 1917; Bleek 1956; Köhler 1963; Baucom 1974; Vossen 1997). During the second half of the 20th century, Khoe languages became the subject of historical-comparative work by Maingard (1961; 1963), Westphal (1962a; 1962b; 1971; 1980), Köhler (1962; 1963; 1966; 1971; 1981), Baucom (1974), Winter (1981; 1986) and Vossen (et al., 1989; 1997). More recently, advances in morphological and phonological reconstruction have established a historical link between Khoe and the extinct Angolan language isolate Kwadi (Güldemann 2004; Güldemann & Elderkin 2010; Fehn & Rocha 2023; Collins & Fehn 2025).

Both qualitative and quantitative approaches agree in supporting a deep split between the Khoe and Kwadi branches, as well as a further subdivision of Khoe into a Khoekhoe and a Kalahari Khoe subgroup (Figure 2) (Vossen 1997; Fehn & Rocha 2023; Fehn et al. 2025).

The present database

2.1 The linguistic data

This database presents lexical data from 29 Khoe-Kwadi varieties from the Kwadi, Kalahari Khoe and Khoekhoe subgroups, which are best understood as “doculects”, i.e., linguistic varieties described in a particular source (published data) or a given documentary context (newly collected data). It should, however, be noted that we sometimes opted to merge data from different sources for a single variety if we could affirm spatiotemporal continuity between datasets (as, e.g., in the cases of Danisi and Deti).

As little is known about the former diversity of the now extinct Southern Khoekhoe varieties known as !Ora or Korana, we kept the three existing sources (Wuras 1920; Engelbrecht 1928; Meinhof 1930) separate. Forms for the Northern Khoekhoe varieties Damara and Haiǁom are only provided if they differ from (Standard) Khoekhoegowab.

Kwadi data is provided according to the reconstituted forms published in Fehn & Rocha (2023); the original transcriptions as contained in the notes and recordings of A. de Almeida, E.O.J. Westphal, and G. Gibson can be accessed online.

The doculects can further be grouped into 9 languages or language clusters (cf. Fehn et al. 2025), as summarised in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Khoe-Kwadi-internal affiliation and sources for doculects included in the present database

| Branch | Language (cluster) | Doculect | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kwadi | Kwadi | Kwadi | Fehn & Rocha (2023) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Khwe-ǁAni | ǁAni | Fehn et al. (2024a) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Khwe-ǁAni | Khwe | Kilian-Hatz (2003) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Khwe-ǁAni | Buga | Fehn & Rocha (2022-2024) Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Khwe-ǁAni | G|anda | Fehn & Rocha (2022-2024) Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Ts'ixa | Ts'ixa | Fehn et al. (2024b) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Shua | Danisi | Fehn et al. (2024c) Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Shua | Gǁoro | Fehn et al. (2024c) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Shua | Cara | Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Shua | Nata-Shua | Fehn et al. (2024c) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Shua | |Xaise | Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Shua | Deti | Fehn et al. (2024c) Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Tshwa | Tjwao | Phiri (2014-2021) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Tshwa | Koßee | Westphal (1953-1971) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Tshwa | Gǁabakʼe | Westphal (1953-1971) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Tshwa | Hiechware | Dornan (1917) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Tshwa | Cua | Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Tshwa | Tsua | Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Tshwa | Kua | Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Gǀui-Gǁana | Gǁana | Vossen (1997) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Gǀui-Gǁana | Gǀui | Nakagawa et al. (2023b) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Naro | Naro | Visser (2001) |

| Kalahari Khoe | Naro | ǂHaba | Vossen (1997) Nakagawa (2017) |

| Khoekhoe | Northern Khoekhoe | Khoekhoegowab | Haacke & Eiseb (2002) |

| Khoekhoe | Northern Khoekhoe | Damara | Haacke & Eiseb (2002) |

| Khoekhoe | Northern Khoekhoe | Haiǁom | Haacke & Eiseb (2002) |

| Khoekhoe | Southern Khoekhoe | !Ora | Meinhof (1930) |

| Khoekhoe | Southern Khoekhoe | !Ora | Engelbrecht (1928) |

| Khoekhoe | Southern Khoekhoe | !Ora | Wuras (1920) |

2.2 Orthographical conventions

To facilitate comparison, all data was retransliterated from original sources into a unifying orthography. Where available, the original orthography was retained and is provided alongside the retransliterated version. We opted for using orthographical conventions widespread in the transcription of Khoe-Kwadi languages which may contain some idiosyncrasies, but broadly follow recommendations by the International Phonetic Association (IPA). In Table 2 below, we note the most important conventions used for click consonants and vowels, which either deviate from standard IPA, or involve symbols the non-specialist reader may be unfamiliar with.

Table 2: Orthographical conventions in this database, contrasted with others used in the transcription of southern African click languages; the alveolar click <!> is used here to exemplify all click types.

| This database | Superscript | Diacritics (IPA) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| ! | ᵏ! | !̥ | plain |

| g! | ᶢ! | !̬ | voiced |

| ŋ! | ᵑ! | !̬̃ | nasal |

| ŋg! | ᵑᶢ! | ŋ!̬ | prenasalised-voiced |

| !ʰ | ᵏ!ʰ | aspirated | |

| !h | ᵑ̊!ʰ | delayed aspirated | |

| !ˀ | ᵑ̊!ˀ | glottalized | |

| !’ (regular) or !k’ (delayed ejection) |

ᵏ!’ | ejective | |

| !x (velar) or !χ (uvular) |

ᵏ!͡χ | affricated | |

| !x’ (velar) or !χ’ (uvular) |

!͡χ ’ | affricated ejective | |

| !q | !͡q | uvular | |

| !ɢ | ᶢ!͡ɢ | uvular voiced | |

| !q’ | !͡q ’ | uvular ejective | |

| !qʰ | !͡qʰ | uvular aspirated | |

| ã | aⁿ | ã | nasal vowel |

| aˤ | aˤ | a̰ | pharyngealized vowel |

In addition, we use the following symbols to denote reconstructed phonemes with uncertain properties (Table 3):

Table 3: Orthographical conventions used in this database to denote reconstructed phonemes with uncertain properties

| This database | Description |

|---|---|

| Ʞ | Unknown click type |

| TS | Unknown consonant synchronically reflected by an alveolar affricate /ts/ or a dental click /ǀ/ |

| H | Unknown type of aspiration |

| X | Unknown type of affricate or affrication |

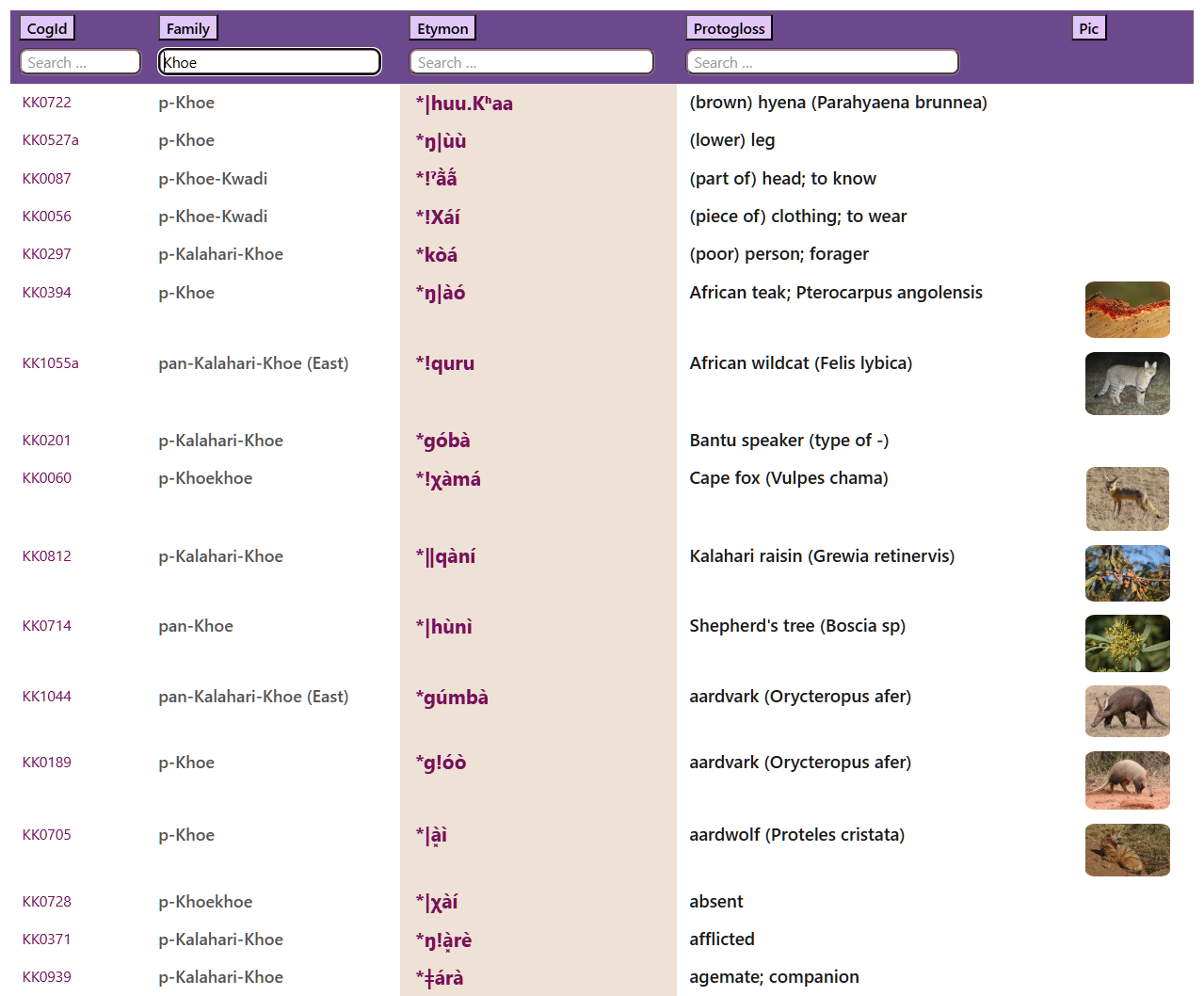

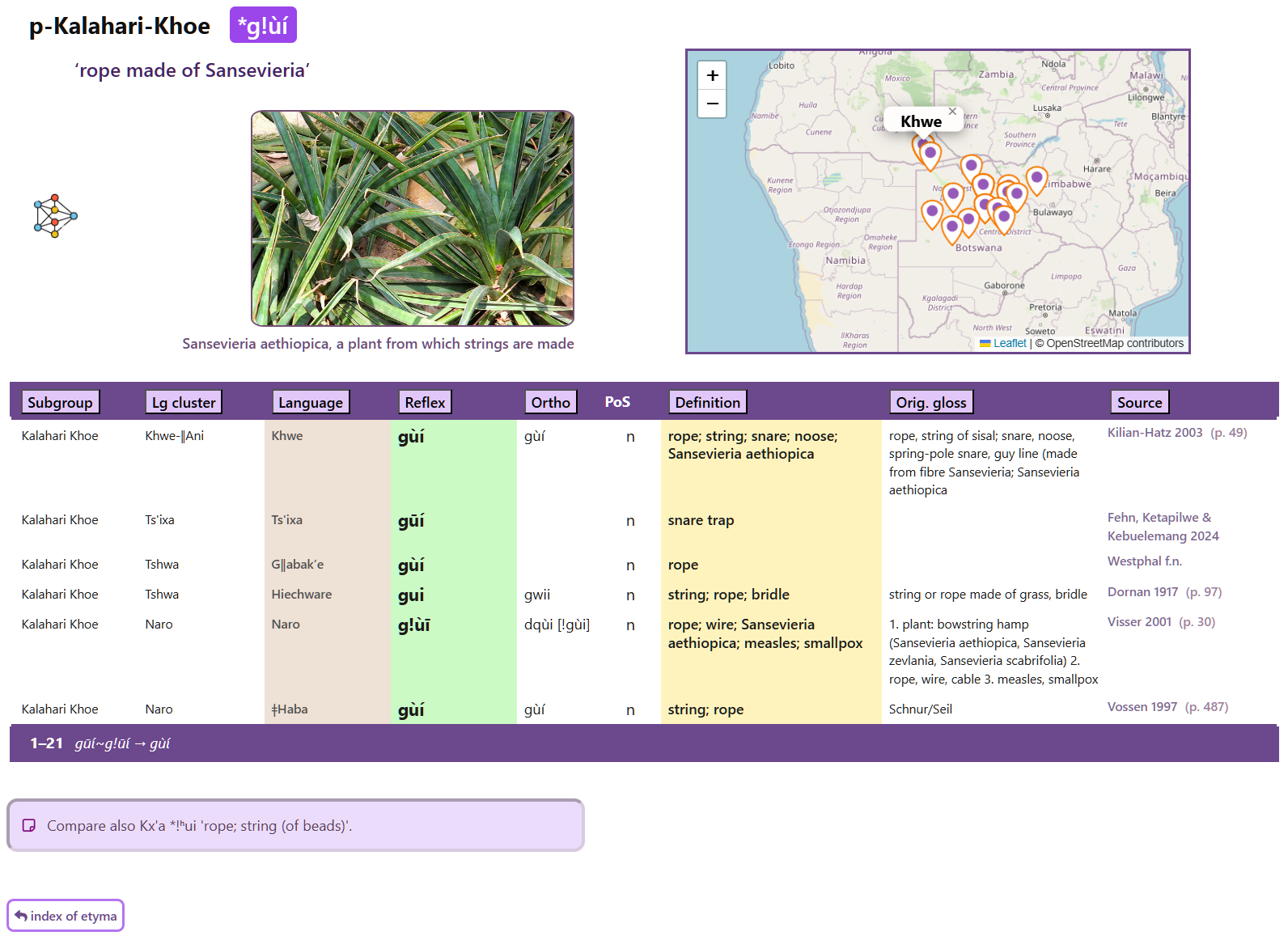

2.3 Using this dictionary

The present dictionary follows the general layout of the 𝓔𝓿𝓸𝕃𝕖𝕩 series of comparative dictionaries, whose general principles are presented in its own homepage. We sum up here the main aspects.

An 𝓔𝓿𝓸𝕃𝕖𝕩 dictionary consists at least of two page types:

- an index of etyma as reconstructed for certain protolanguages [example]

-

and, (if you click on one of the “etyma” on that list)

a detailed entry displaying the entire cognate set under that etymon [example]

For detailed explanations about the structure of such entries, see the general introduction to the 𝓔𝓿𝓸𝕃𝕖𝕩 series of comparative dictionaries.

2.4 Reconstructions

The data is presented in the form of correspondence sets, i.e., lexical forms are grouped by shared origin, rather than by shared meaning. This format carries the advantage of showcasing regular correspondences between individual doculects while also documenting etymological change within the family. For each correspondence set, we present the assumed underlying form, which may either be a genuine reconstruction (“proto”-form) or a non-reconstructable root with wider distribution in Khoe-Kwadi (“pan”-form).

In addition, we present forms with restricted distribution, which may – but do not necessarily need to – go back to inherited “proto”-forms. Each reconstructed form (or “etymon”) is linked to the deepest level of reconstruction, i.e., proto-Khoe-Kwadi, proto-Khoe, proto-Kalahari-Khoe and proto-Khoekhoe. As the subclassification of Kalahari Khoe is a matter of ongoing research, we also note reconstructions valid for areal subsets of Kalahari Khoe, i.e., Kalahari-Khoe (North), Kalahari-Khoe (South), Kalahari-Khoe (East) and Kalahari-Khoe (West).

2.4.1. Reconstructing tone

Reconstructions presented in this work take into account regular sound correspondences noted in previous works (especially in Vossen 1997; Elderkin 2004, 2016, 2020; Fehn & Rocha 2023). Specifically, vowel and tone reconstructions follow Elderkin (2016) and Elderkin (2004), respectively. As the limited set of Kwadi recordings does not allow for a comprehensive tonal analysis of proto-Khoe-Kwadi, all tonal reconstructions provided for the proto-Khoe-Kwadi stage refer to proto-Khoe. Moreover, tonal reconstructions for proto-Khoe, proto-Kalahari-Khoe and proto-Khoekhoe only follow languages for which reliable tone marking is available, i.e., Khoekhoegowab (Haacke & Eiseb 2002), Naro (Visser 2001), Gǀui (Nakagawa et al. 2023), Khwe (Kilian-Hatz 2003), ǁAni (Fehn et al. 2024a), Ts’ixa (Fehn et al. 2024b) – as well as various dialects of Shua recorded during the survey of Fehn et al. (2024c).

We thereby follow Elderkin (2004) in reconstructing two tone levels, High and Low, for the proto-Khoe-stage, based on three tone levels (High, Mid and Low) attested throughout Kalahari Khoe, and four tone levels (extra-Low, Low, High, extra-High) in Khoekhoegowab. We further assume that the tone-bearing unit is the mora, and that Khoe-Kwadi lexical roots are inherently bimoraic (Elderkin 2004); in consequence, we have retransliterated monomoraic forms noted in some sources to contain two morae, e.g., pá ‘bite’ > páá (Khwe; Kilian-Hatz 2003: 103).

2.4.2. Reconstructing consonants

The reconstruction of click and non-click consonants differs from previous works in four major aspects.

First, we assume a palatal stop series (*c, *ɟ, *cʰ, *c’) for the proto-Khoe-Kwadi and proto-Khoe stages to account for a set of correspondences which were noted as featuring an unknown onset (*K, *Kʰ, *K’) in Fehn and Rocha (2023). Synchronic reflexes thereby suggest two main trajectories of sound change: one involving lenition from stop to affricate and eventually fricative (1); the other involving a shift in place of articulation, from palatal to velar (2). Velarisation generally affects the palatal ejective, but is otherwise only attested with a subset of Khoekhoe forms.

| (1) | Stop | Affricate | Fricative |

|---|---|---|---|

| *c > | /ʧ/ > /ts/ | > /s/ > /θ/ | |

| *ɟ > | /ʤ/ > /dz/ | ||

| *cʰ > | /ʧʰ/ > /tsʰ/ > /ts/ | > /s/ |

| (2) | Palatal | Velar |

|---|---|---|

| *c > | /k/ | |

| *cʰ > | /kʰ/ | |

| *c’ > | /k’/ > /kχ’/ |

Two further examples (*cʰè͓è ‘bow’ and *cʰànì ‘stand up’) display an aspirated velar stop /kʰ/ in Khoekhoe, and an alveolar stop /t/ with tonal depression in Kalahari Khoe, possibly suggesting further involvement of an unknown kind of phonation in the proto-language.

An overview of all attested reflexes of underlying palatals across Khoe-Kwadi is provided in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Reflexes of Proto-Khoe(-Kwadi) palatal stops across the family

| Kwadi | Kalahari Khoe | Khoekhoe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| *c | /ts/~/s/~/θ/ | *ts (or *ʧ) | *s ~ *k |

| *ɟ | /dz/ | *dz (or *ʤ) | *ts (or *dz) |

| *cʰ | /s/ | *tsʰ (or *ʧʰ) ~ *tV͓ | *ts ~ *s ~ *kʰ |

| *c’ | /c’/ | *kχ’ (or *c’) | *kχ’ |

Second, we find evidence for two types of aspirated clicks at the proto-Khoe stage, namely regular (*!ʰ) and delayed (*!h) aspiration: both types have been merged into delayed aspiration (*!h) in Khoekhoe, while Kalahari-Khoe appears to have initially retained a two-way distinction between regular (*!ʰ) and delayed (*!h) aspiration; however, modern languages reflect the latter by a plain or nasalised click, followed by a depressed tonal melody. In addition, there are two correspondence sets which suggest that at least one type of aspirated click already existed at the proto-Khoe-Kwadi stage; for lack of conclusive evidence on the nature of the underlying sound, we reconstruct *!H, whereby <H> stands for an unknown type of aspiration.

Third, we only assume the existence of one nasal click series at all stages of reconstruction. While Vossen (1997) reconstructs both nasalised (*ŋ!) and prenasalised voiced (*ŋg!) clicks for the proto-Khoe and proto-Kalahari-Khoe stages, we here follow Elderkin (2020) in considering prenasalised voiced clicks as allophones of nasalised clicks in environments preceding a non-nasal rhyme.

Finally, we assume that both voiceless and voiced uvular stops (*q, *ɢ) and click accompaniments existed as peripheral consonants at the proto-Khoe stage; while most Kalahari-Khoe language clusters retained at least a subset of uvular sounds, they were lost entirely in all known Khoekhoe varieties.

2.4.3. Unspecified consonants

Our reconstructions further contain a number of unspecified sounds for which we could not satisfactorily resolve the place and type of articulation.

Most notably, no underlying sound could yet be associated with a set of split-correspondences linking a subset of proto-Khoe alveolar and lateral clicks to uvular fricatives (/χ/) and ejectives (/qχ’/) in Kwadi (Fehn & Rocha 2023). While it seems plausible that proto-Khoe-Kwadi had a fifth click type, it might also be suggested that the uvular click replacements merely reflect [+back] clicks with a uvular accompaniment, whereby the click type as such was lost. Due to our inability to resolve this issue, we here follow Fehn & Rocha (2023) in noting an unknown click type *Ʞ for proto-Khoe-Kwadi roots with irregular reflexes in proto-Khoe.

Similarly, while some Kwadi forms featuring an affricate or fricative correspond to proto-Khoe clicks with affricated accompaniments, it is not clear whether velar or uvular friction – or even delayed aspiration – should ultimately be reconstructed for the proto-Khoe-Kwadi stage. We therefore write <X> to denote a fricative or fricated click accompaniment in proto-Khoe-Kwadi, without adopting a final opinion on its de facto phonological value.

For the proto-Khoe, proto-Kalahari-Khoe and proto-Khoekhoe stages, we consistently reconstruct uvular fricatives (*χ), as well as uvular affrication for velar ejectives (*kχ’), affricated clicks (*!χ) and affricated ejective clicks (*!χ’). We note, however, that the uvularisation may be a secondary feature which was adopted in contact with languages of the Kx’a and Tuu families; in this scenario, *x, *k(x)’, *!x and *!x’ should be reconstructed instead.

For both the proto-Khoe-Kwadi and the proto-Khoe stage, we further reconstruct an unknown type of onset noted as <TS>, which yielded alveolar affricates (*ts, *ts’) in proto-Kalahari-Khoe, and dental clicks in proto-Khoekhoe (*ǀχ, *ǀχ’). Kwadi shows split-correspondences, sometimes displaying affricates, and sometimes clicks. While previous studies have interpreted the underlying sound as either alveolar affricate (Vossen 1997, Traill & Vossen 1997) or dental click (Fehn 2020), it is well possible that the synchronic reflexes derive from an entirely different kind of sound (such as an implosive) which no longer survives in any contemporary language of the area.

2.5 Consonant inventories of proto-languages

The correspondence sets provided in this database allow us to establish reconstructed phoneme inventories for the proto-Khoe-Kwadi, proto-Khoe, proto-Kalahari-Khoe and proto-Khoekhoe stages. General continuity can be observed for the vowel inventory, which consists of five oral */a, e, i, o, u/ and three nasal vowels */ĩ, ã, ũ/ at all proto-stages. For a discussion of historical correspondences between vowel sequences in different consonantal environments, the reader is referred to Elderkin (2016) and Fehn & Rocha (2023).

The reconstructed consonant inventories can be divided into non-click (Tables 5, 7, 9, 11) and click inventories (Tables 6, 8, 10, 12), whereby four click types are minimally distinguished at all proto-stages. Each click can appear with a set of different accompaniments, which range between (at least) seven at the proto-Khoe-Kwadi (Table 6) and proto-Khoekhoe (Table 12) stages, and ten at the proto-Khoe (Table 8) and proto-Kalahari-Khoe (Table 10) stages. Due to the limited size of individual datasets, in particular for Kwadi, reconstructed click inventories may display gaps in the attestation of accompaniments for all four click types.

Table 5: Non-click consonant inventory of proto-Khoe-Kwadi (adapted from Fehn & Rocha 2023); in addition, proto-Khoe-Kwadi had a voiceless fricative with unidentified place of articulation (*X), and an unspecified click or non-click ejective consonant (*TS’).

| bilabial | alveolar | lateral | velar | palatal | glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STOP | voiceless | *p | *t | *k | *c | *ʔ | |

| voiced | *b | *d | *g(ʷ) | *ɟ | |||

| aspirated | *tʰ | *kʰ | *cʰ | ||||

| ejective | *t’ | *k’ | *c’ | ||||

| FRICATIVE | voiceless | *s | *h | ||||

| NASAL | voiced | *m | *n | ||||

| TRILL | voiceless | *r |

Table 6: Click inventory of proto-Khoe-Kwadi (adapted from Fehn & Rocha 2023)

| dental | alveolar | lateral | palatal | unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless | *ǀ | *! | *ǁ | *ǂ | *Ʞ |

| voiced | *gǀ | *g! | *gǁ | *ǂg | |

| nasal | *ŋǀ | *ŋǁ | |||

| aspirated | *!H | ||||

| glottalised | *ǀˀ | *!ˀ | *ǁˀ | *ǂˀ | *Ʞˀ |

| affricated | *ǀX | *!X | *ǁX | *ǂX | |

| (affricated) ejective | *ǀ(X)ʼ | *ǁ(X)ʼ | *ǂ(X)ʼ |

Table 7: Non-click consonant inventory of proto-Khoe (based on the present database); in addition, proto-Khoe had an unspecified affricate or affricated click (*TS), and an affricated ejective or affricated ejective click (*TS’).

| bilabial | alveolar | lateral | velar | palatal | uvular | glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STOP | voiceless | *p | *t | *k | *c | *q | *ʔ | |

| voiced | *b | *d | *g | *ɟ | *ɢ | |||

| aspirated | *tʰ | *kʰ | *cʰ | |||||

| ejective | *tʼ | *kχʼ | *c’ | |||||

| FRICATIVE | voiceless | *s | *χ | *h | ||||

| NASAL | voiced | *m | *n | |||||

| TRILL | voiceless | *r |

Table 8: Click inventory of proto-Khoe (based on the present database)

| dental | alveolar | lateral | palatal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless | *ǀ | *! | *ǁ | *ǂ |

| voiced | *gǀ | *g! | *gǁ | *gǂ |

| nasal | *ŋǀ | * ŋ! | *ŋǁ | *ŋǂ |

| aspirated | *ǀʰ | *!ʰ | *ǁʰ | *ǂʰ |

| delayed aspirated | *ǀh | *!h | *ǁh | *ǂh |

| glottalised | *ǀˀ | *!ˀ | *ǁˀ | *ǂˀ |

| affricated | *ǀχ | *!χ | *ǁχ | *ǂχ |

| affricated ejective | *ǀχʼ | *!χʼ | *ǁχʼ | *ǂχʼ |

| uvular | *ǀq | *ǁq | *ǂq | |

| uvular voiced | *ǁɢ |

Table 9: Non-click consonant inventory of proto-Kalahari-Khoe (based on the present database)

| bilabial | alveolar | lateral | palatal | velar | uvular | glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STOP | voiceless | *p | *t | *k | *q | *ʔ | ||

| voiced | *b | *d | *g | *ɢ | ||||

| aspirated | *tʰ | *kʰ | ||||||

| ejective | *tʼ | *kχʼ | ||||||

| AFFRICATE | voiceless | *ts | ||||||

| voiced | *dz | |||||||

| aspirated | *tsʰ | |||||||

| affricated | *tsχ | |||||||

| ejective | *tsʼ | |||||||

| FRICATIVE | voiceless | *s | *χ | *h | ||||

| NASAL | voiced | *m | *n | |||||

| TRILL | voiceless | *r | ||||||

| APPROXIMANT | voiceless | *j |

Table 10: Click inventory of proto-Kalahari-Khoe (based on the present database)

| dental | alveolar | lateral | palatal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless | *ǀ | *! | *ǁ | *ǂ |

| voiced | *gǀ | *g! | *gǁ | *gǂ |

| nasal | *ŋǀ | * ŋ! | *ŋǁ | *ŋǂ |

| aspirated | *ǀʰ | *!ʰ | *ǁʰ | *ǂʰ |

| delayed aspirated | *ǀh | *!h | *ǁh | *ǂh |

| glottalised | *ǀˀ | *!ˀ | *ǁˀ | *ǂˀ |

| affricated | *ǀχ | *!χ | *ǁχ | *ǂχ |

| affricated ejective | *ǀχʼ | *!χʼ | *ǁχʼ | *ǂχʼ |

| uvular | *ǀq | *!q | *ǁq | *ǂq |

| uvular voiced | *ǀɢ | *ǁɢ | *ǂɢ |

Table 11: Non-click consonant inventory of proto-Khoekhoe (based on the present database)

| bilabial | alveolar | lateral | velar | uvular | glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STOP | voiceless | *p | *t | *k | *ʔ | ||

| voiced | *b | *d | *g | ||||

| aspirated | *tʰ | *kʰ | |||||

| ejective | *kχʼ | ||||||

| AFFRICATE | voiceless | *ts | |||||

| FRICATIVE | voiceless | *s | *χ | *h | |||

| NASAL | voiced | *m | *n | ||||

| TRILL | voiceless | *r |

Table 12: Click inventory of proto-Khoekhoe (based on the present database)

| dental | alveolar | lateral | palatal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless | *ǀ | *! | *ǁ | *ǂ |

| voiced | *gǀ | *g! | *gǁ | *gǂ |

| nasal | *ŋǀ | * ŋ! | *ŋǁ | *ŋǂ |

| delayed aspirated | *ǀh | *!h | *ǁh | *ǂh |

| glottalised | *ǀˀ | *!ˀ | *ǁˀ | *ǂˀ |

| affricated | *ǀχ | *!χ | *ǁχ | *ǂχ |

| affricated ejective | *ǀχʼ | *!χʼ | *ǁχʼ | *ǂχʼ |

Conclusion and outlook

This database provides updated lexical reconstructions for the Khoe-Kwadi language family, based on contemporary and historical data from 29 doculects recorded in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Angola and Zimbabwe. It extends the existing corpus of available reconstructions for all proto-stages (proto-Khoe-Kwadi, proto-Khoe, proto-Kalahari-Khoe, proto-Khoekhoe) and provides correspondence sets based on a large amount of carefully transcribed and curated data.

As Khoe-Kwadi has been linked to the pre-Bantu introduction of sheep-based pastoralism from eastern into southern Africa, scholars from such diverse disciplines as archaeology, genetics and linguistics have sought to unravel the family’s link with early food production and the emergence of social hierachies. We hope that the reconstructions provided in this database will help to shed further light on the history of Khoe-Kwadi and its speakers, in particular with regards to domestic animals, pastoral practices, and objects of material culture.

Furthermore, the compiled presentation of lexical data linked to both reconstructions and non-reconstructable but widespread lexical forms is expected to contribute to a better understanding of contact relations within the Kalahari Basin linguistic area. Our data provides a first step in reliably distinguishing inherited from borrowed vocabulary, and allows for an assessment of early borrowings into diverse proto-stages of the Khoe-Kwadi family. In addition, it offers a readily available and historically sound source for scholars seeking to identify Khoe-Kwadi borrowings into southern African Bantu and non-Bantu languages.

We hope that in the future, this database will continue to grow through the addition of newly collected linguistic data, as well as through the identification of further reconstructions and the contextualisation with other historical datasets from the area, especially from the Kx’a and Tuu language families.

Anne Maria Fehn, Nov 2025.

About the authors

Anne-Maria Fehn

1 CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, InBIO Laboratório Associado, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal.

2 Biopolis Program in Genomics, Biodiversity and Land Planning, CIBIO, Vairão, Portugal.

2 Biopolis Program in Genomics, Biodiversity and Land Planning, CIBIO, Vairão, Portugal.

Anna Smirnitskaya

3 Department of Asian and African languages, Institute of Oriental Studies, Moscow, Russia.

Tshisimogo Leepang

1 CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, InBIO Laboratório Associado, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal.

2 Biopolis Program in Genomics, Biodiversity and Land Planning, CIBIO, Vairão, Portugal.

2 Biopolis Program in Genomics, Biodiversity and Land Planning, CIBIO, Vairão, Portugal.

4 University of Botswana,Gaborone, Botswana.

Hirosi Nakagawa

5 Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Tokyo, Japan.

Admire Phiri

1 CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, InBIO Laboratório Associado, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal.

1 CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, InBIO Laboratório Associado, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal.

2 Biopolis Program in Genomics, Biodiversity and Land Planning, CIBIO, Vairão, Portugal.

6 Department of Linguistics, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Jorge Rocha

1 CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, InBIO Laboratório Associado, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal.

2 Biopolis Program in Genomics, Biodiversity and Land Planning, CIBIO, Vairão, Portugal.

7 Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal.

References

Baucom, Kenneth L. 1974. Proto-Central Khoisan. In Erhard Voeltz (ed.), Third Annual Conference on African Linguistics, 7-8 April 1972, 3–37. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University.

Bleek, Dorothea F. 1956. A Bushman dictionary. American Oriental Society.

Brenzinger, Matthias. 2013. The twelve modern Khoisan languages. In Alena Witzlack-Makarevich & Martina Ernszt (eds.), Khoisan languages and linguistics: Proceedings of the 3rd international symposium, July 6–10, 2008, Riezlern/Kleinwalsertal. Edited by, 139–161. Research in Khoisan Studies 29. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

den Besten, Hans. 2010. A badly harvested field: The growth of linguistic knowledge and the Dutch Cape colony until 1796. In Siegfried Huigen, Jan L. de Jong, Elmer Kolfin, et al. (eds.), The Dutch Trading Companies as Knowledge Networks (Intersections – Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture 14), 267-294. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

Collins, Chris & Anne-Maria Fehn. 2025. Parameters of Morphosyntactic Variation in Khoe-Kwadi. Transactions of the Philological Society 123(2): 246-279. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-968X.12315

Dornan, Samuel S. 1917. The Tati Bushmen (Masarwas) and their language. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 47(1): 37-112.

Elderkin, Edward D. 2004. The starred tones of Central Khoisan. Afrika und Übersee 87: 3–77.

Elderkin, Edward D. 2016. The vowel system of proto-Khoe. In Sheena Shah & Matthias Brenzinger (eds.), Khoisan languages and linguistics. Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium in Riezlern/Kleinwalsertal, 53–95. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Elderkin, Edward D. 2020. Nasalized accompaniments in Proto-Khoe and in Khwe. In Bonny Sands (ed.), Click consonants, 275–290. Leiden: Brill.

Engelbrecht, Jan A. 1928. Studies oor Korannataal (Annale van die universiteit van stellenbosch, 6). Cape Town: Nasionale Pers.

Fehn, Anne-Maria. 2020. Click loss in Khoe-Kwadi. In Bonny Sands (ed.), Click consonants, 291–335. Leiden: Brill.

Fehn, Anne-Maria, Amorim, Amorim & Jorge Rocha. 2022. The linguistic and genetic landscape of southern Africa. Journal of Anthropological Sciences 100: 243–265.

Fehn, Anne-Maria & Jorge Rocha. 2022-2024. Khwe dialect survey. Data recorded at Kaputura & Gudigwa, Botswana. Unpublished fieldnotes.

Fehn, Anne-Maria, & Jorge Rocha. 2023. Lost in translation: A historical-comparative reconstruction of Proto-Khoe-Kwadi based on archival data. Diachronica, 40(5): 609–665. https://doi.org/10.1075/dia.23022.feh

Fehn, Anne-Maria, Mogomotsi, Mmoloki & Kelatlhilwe Gamaxo Moses. 2024a. A Dictionary of ǁAnikhwedam. Manuscript Version. Vairão: Network of CIBIO-InBIO TwinLabs in Africa.

Fehn, Anne-Maria, Ketapilwe, Arnold & Tshiamo Kebuelemang. 2024b. A dictionary of Ts’ixa: a Khoe language of northern Botswana. Manuscript Version. Vairão: Network of CIBIO-InBIO TwinLabs in Africa.

Fehn, Anne-Maria, Leepang, Tshisimogo & Jorge Rocha. 2024c. Shua dialect survey. Data recorded at Mopipi, Botswana. Unpublished fieldnotes.

Fehn, Anne-Maria, Sands, Bonny, Phiri, Admire, Bolaane, Maitseo, Masunga, Gaseitsiwe & Jorge Rocha. 2025. Tracing contact and migration in pre-Bantu southern Africa through lexical borrowing. Evolutionary Human Sciences 7: e25. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2025.10014

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1963. The languages of Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University.

Güldemann, Tom. 1998. The Kalahari Basin as an object of areal typology: a first approach. In Matthias Schladt (ed.), Language, identity and conceptualisation among the Khoisan, 137–169. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Güldemann, Tom. 2004. Reconstruction through ‘de-construction’: The marking of person, gender, and number in the Khoe family and Kwadi. Diachronica 21(2): 251–306. https://doi.org/10.1075/dia.21.2.02gul.

Güldemann, Tom. 2008. A linguist’s view: Khoe-Kwadi speakers as the earliest food-producers of southern Africa. In Karim Sadr & François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar (eds.), Khoekhoe and the earliest herders in southern Africa (Southern African Humanities 20), 93–132.

Güldemann, Tom & Edward D. Elderkin. 2010. On external genealogical relationships of the Khoe family. In Matthias Brenzinger & Christa König (eds.), Khoisan languages and linguistics. Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium, January 4-8, 2003, Riezlern/Kleinwalsertal, 15–52. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Güldemann, Tom & Anne-Maria Fehn. 2017. The Kalahari Basin Area as a ‘Sprachbund’ before the Bantu expansion. In R. Hickey (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of areal linguistics, 500–526. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haacke, Wilfrid H.G. & Eliphas Eiseb. 2002. A Khoekhoegowab dictionary with an English-Khoekhoegowab index. Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan.

Kilian-Hatz, Christa. 2003. Khwe dictionary (Namibian African Studies, 7). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Köhler, Oswin. 1962. Studien zum Genussystem und Verbalbau der zentralen Khoisan-Sprachen. Anthropos 57: 529–546.

Köhler, Oswin. 1963. Observations on the Central Khoisan language group. Journal of African Languages 2(3): 227–234.

Köhler, Oswin. 1966. Die Wortbeziehungen zwischen der Sprache der Kxoe-Buschmänner und dem Hottentottischen als geschichtliches Problem. In Johannes Lukas (ed.), Hamburger Beiträge zur Afrika Kunde, Band 5, 144–165. Hamburg: Deutsches Institut für Afrika-Forschung.

Köhler, Oswin. 1971. Die Khoe-sprachigen Buschmänner der Kalahari. Ihre Verbreitung und Gliederung. In Forschungen zur allgemeinen und regionalen Geographie (Festschrift für Kurt Kayser), 373–411. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner.

Köhler, Oswin. 1981. Les langues khoisan. (Ed.) Jean Perrot & Gabriel Manessy. Paris: Editions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Maingard, Ludwig F. 1961. The central group of click languages of the Kalahari. African Studies 20: 114–122.

Maingard, Ludwig F. 1963. A comparative study of Naron, Hietshware and Korana. African Studies 22: 97–108.

Meinhof, Carl. 1930. Der Koranadialekt des Hottentottischen (Beiheft zur Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen, 12). Hamburg: Dietrich Reimer.

Nakagawa, Hirosi. 2017. ǂHaba Tonology. In Anne-Maria Fehn (ed.), Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium July 11-13, 2011, Riezlern/Kleinwalsertal, 109-119. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Nakagawa, Hirosi, Witzlack-Makarevich, Alena, Auer, Daniel, Fehn, Anne-Maria, Ammann Gerlach, Linda, Güldemann, Tom, Job, Sylvanus, Lionnet, Florian, Naumann, Christfried, Ono, Hitomi & Pratchett, Lee James. 2023a. Towards a phonological typology of the Kalahari Basin Area languages. Linguistic Typology 27(2): 509–535. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2022-0047

Nakagawa, Hirosi, Sugawara, Kazuyoshi & Jiro Tanaka. 2023b. A Gǀui Dictionary. Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Unpublished Manuscript.

Phiri, Admire. 2014-2021. Tjwao fieldnotes. Data recorded at Tsholotsho, Zimbabwe. Unpublished fieldnotes.

Traill, Anthony & Rainer Vossen. 1997. Sound change in the Khoisan languages: new data on click loss and click replacement. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 18: 21–56.

Visser, Hessel. 2001. Naro dictionary: Naro - English, English - Naro. D'Kar: Naro Language Project.

Vossen, Rainer. 1997. Die Khoe-Sprachen: Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der Sprachgeschichte Afrikas. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Vossen, Rainer, Neumann, Sabine, Patriarchi, Christina, Rottland, Margit, Sporl, Rainer & Beate Vagt. 1989. Khoe linguistic relationships reconsidered. Botswana Notes and Records 20: 61-70.

Westphal, Ernst O.J. 1953-1971. The E.O.J. Westphal papers. Manuscript collection. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

Westphal, Ernst O. J. 1962a. A re-classification of Southern African non-Bantu languages. Journal of African Languages 1: 1–18.

Westphal, Ernst O. J. 1962b. On classifying Bushman and Hottentot languages. African Language Studies 3: 30–48.

Westphal, Ernst O. J. 1971. The click languages of southern and eastern Africa. In T.A. Sebeok (ed.), Linguistics in sub-Saharan Africa, 467–420. Den Haag: Mouton.

Westphal, Ernst O. J. 1980. The age of “Bushman” languages in southern African pre-history. In Jan W. Snyman (ed.), Bushman and Hottentot linguistic studies, 59–79. Pretoria: University of South Africa.

Winter, Jürgen C. 1981. Die Khoisan-Familie. In Bernd Heine, Thilo C. Schadeberg & Ekkehard Wolff (eds.), Die Sprachen Afrikas, 329–3754. Hamburg: Helmut Buske.

Winter, Jürgen C. 1986. Les parlers du khoisan central. In Gladys Guarisma & Wilhelm J. G. Möhlig (eds.), La méthode dialectométrique appliquée aux langues africaines, 395–431. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

Wuras, Carl Friedrich. 1920. Vokabular der Korana-Sprache; herausgegeben und mit kritischen Anmerkungen versehen von Walther Borquin (Beiheft zur Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen, 1). Berlin/Hamburg: Dietrich Reimer.

comparative dictionary of

comparative dictionary of